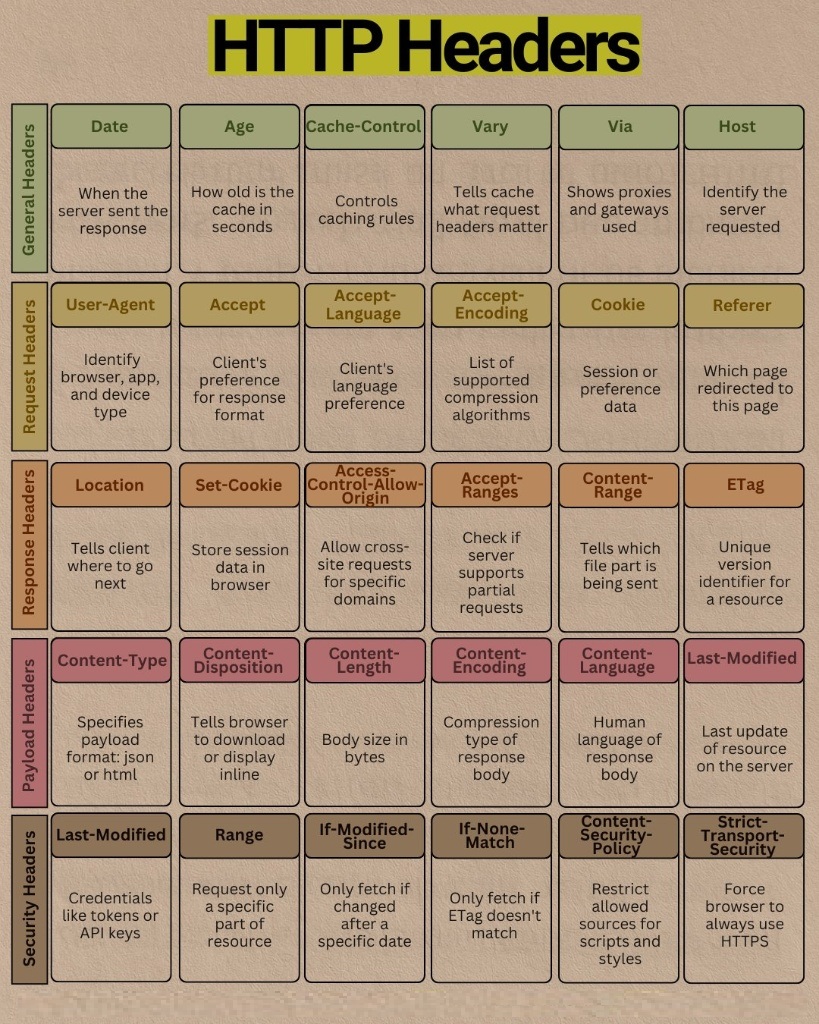

One Diagram to Understand Core HTTP Headers

Decoding the Internet's Whisper: One Diagram to Understand Core HTTP Headers

Whenever you type a URL into your browser and hit Enter, the browser sends a request to the server. The server then replies with a response. The exchange of information between the client and server is governed by a set of HTTP headers. This infographic shows the most important headers and explains what they do.

⬆️ Request Headers: The Client's "Checklist of Needs"

- User-Agent: The client's self‑introduction. It tells the server “who I am”, e.g., “Chrome on Windows 11” or “Safari on an iPhone”. The server can use this to provide tailored content (e.g., a mobile version of the page).

- Accept: The client tells the server which content types it can understand, such as

text/html(web pages),application/json(JSON data),image/webp(WebP images). - Accept-Language: The client declares its language preferences, e.g.,

zh-CN, en;q=0.9(preferred Simplified Chinese, then English). The server should return a page in the appropriate language. - Accept-Encoding: The client declares the compression algorithms it supports, such as

gzip, deflate, br. The server will choose one to compress the response body, reducing transfer size. - Cookie: The client sends back data previously stored by the server via

Set-Cookie. This is the core mechanism for maintaining user login state, session tracking, and personalized recommendations. - Referer: Tells the server from which page the user clicked a link to navigate.

⬇️ Response Headers: The Server's "Reply and Instructions"

- Location: When the server returns a redirect status code (e.g., 301 or 302), the

Locationheader tells the browser that the resource you’re looking for is not here and directs it to this new address. - Set-Cookie: The server’s instruction: “Please have the browser store this data (cookie)”. Next time you visit, send it back with the

Cookieheader. - Access-Control-Allow-Origin: The core of the CORS (Cross‑Origin Resource Sharing) mechanism. It declares which other domains are allowed to read this response. Setting it to

*means any domain can. - Accept-Ranges: The server declares whether it supports range requests (i.e., requesting only part of a file). This is essential for large file downloads and video streaming (allowing the progress bar to seek).

- Content-Range: In response to the client’s

Rangerequest, the server uses this header to indicate which part of the file it is sending (e.g.,bytes 21010-47021/47022). - ETag: The resource’s unique version identifier. It’s usually a hash. When the resource content changes, the

ETagchanges as well.

📦 Payload Headers: Detailed Information About the "Cargo"

- Content-Type: Clearly informs the client what the message body actually is. For example,

text/html; charset=utf-8(an HTML document encoded in UTF‑8) orapplication/json. - Content-Length: The exact size of the message body (in bytes).

- Content-Encoding: The server confirms which compression algorithm it actually used (e.g.,

gzip) to compress the response body. The browser will decompress accordingly. - Content-Language: Declares the human language used in the message body content (e.g.,

zh-CN). - Content-Disposition: Indicates how the browser should handle the resource.

inlinemeans it should try to display it directly in the browser (e.g., images, PDFs);attachment; filename="data.zip"prompts the user to download it as an attachment. - Last-Modified: The date and time the resource was last modified on the server.

🛡️ Security & Conditional Headers

The final group (the fifth row in the original diagram) is key to ensuring network security and improving efficiency, blending security directives with conditional requests for efficient caching.

- Authorization: (Note: the original diagram mistakenly labeled this as

Last-Modified, but based on the description “credentials, such as tokens or API keys”, it should beAuthorization). This is how the client proves its identity to the server, typically used for protected API requests, e.g.,Authorization: Bearer <your_jwt_token>. - Range: This is a request header that the client uses to tell the server: “I don’t want the entire file, just this portion (range).”

- If-Modified-Since: This is a conditional request header. After caching a resource, the browser includes this header (with the value of the last received

Last-Modifieddate) to ask the server: “Has this resource been updated since this time?” - If-None-Match: A similar conditional request header, but it uses

ETag. The browser asks: “My local version’sETagis this; is the server’s version different?”

How Does Caching Work?

CombiningETagandIf-None-Match(orLast-ModifiedandIf-Modified-Since):

- The browser requests a resource, and the server returns the resource along with

ETag: "v1".- The browser caches the resource and its

ETag.- On the next request, the browser sends

If-None-Match: "v1".- The server compares the

ETag: If unchanged, it returns a lightweight304 Not Modifiedresponse, and the browser uses the cached copy. If changed, it returns200 OKand the new resource content.

- Content-Security-Policy (CSP): A powerful response header used to mitigate XSS (cross‑site scripting) attacks. It defines a “whitelist” telling the browser only to load scripts, styles, images, etc., from specified sources.

- Strict-Transport-Security (HSTS): An extremely important security response header. It forces browsers to access the site only via HTTPS for a specified period (e.g.,

max-age=31536000, one year), completely eliminating insecure HTTP requests and preventing man‑in‑the‑middle attacks.

Summary

HTTP Headers are like the nervous system of the network, conveying all the contextual information necessary for the modern web to run efficiently and securely. They manage caching, handle authentication, negotiate content formats, and protect us from attacks.

This infographic provides us with a valuable map. Next time you develop or debug network issues, consider recalling these headers—they may hold the key to unraveling the mystery.